Little Nightmares is more than a puzzle-platform horror game; it’s a disturbing, dreamlike reflection of childhood trauma. Beneath its haunting aesthetic and grotesque characters lies a visual story about vulnerability, dependency, and the distorted realities born from fear. Every sound, object, and environment operates as a piece of psychological language. Players don’t merely escape monsters—they traverse symbolic representations of abuse, neglect, and emotional repression. Understanding these symbols transforms the game from a simple horror experience into an exploration of survival in the shadow of trauma.

1. The Language of Fear in Environmental Design

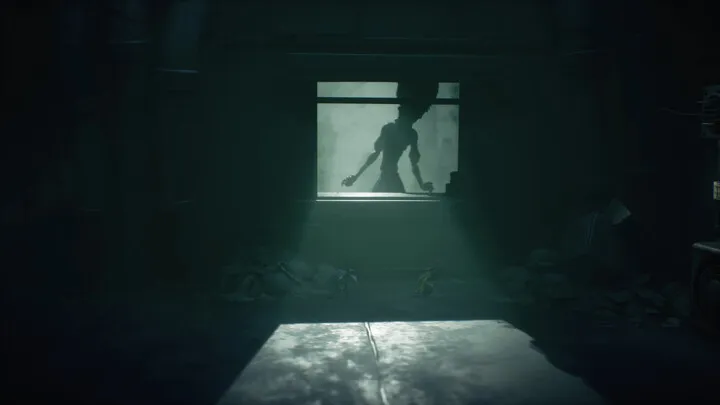

The first layer of symbolism in Little Nightmares comes from the way its environments mirror the emotional reality of a child in distress. The Maw, the game’s setting, operates not as a physical place but as a dreamlike manifestation of fear. Narrow hallways exaggerate claustrophobia, towering furniture emphasizes powerlessness, and muted lighting creates constant unease.

Fear is conveyed through the manipulation of scale. Everything in the world appears oversized, reminding the player that this is seen from the perspective of a small, defenseless being. The massive chairs and hanging utensils suggest adult dominance, where even inanimate objects become symbols of threat.

Lighting as a Metaphor for Uncertainty

The game’s lighting conveys the child’s shifting emotional state. Shadows obscure not just danger but identity—what’s hiding may not always be external. The use of flickering light parallels the instability of memory, implying that fear blurs the boundaries between safety and threat.

2. The Maw as a Representation of Consumption

The Maw, the central location of Little Nightmares, is more than a setting—it’s a metaphor for emotional and physical consumption. Its grotesque inhabitants endlessly gorge themselves, representing the way trauma consumes innocence.

Gluttony as a Reflection of Exploitation

The grotesque feasting scenes mirror how adults in abusive environments “consume” children’s safety, identity, or trust. They drain emotional resources until nothing remains but survival instinct. This continuous feeding cycle becomes the visual equivalent of emotional neglect—excess without nourishment.

The Kitchen Sequence

The twin chefs are a perfect example of predatory consumption. They chop, grind, and boil without awareness or empathy, embodying how institutional systems—families, schools, societies—process children into conformity or silence.

3. The Symbolism of Smallness and Helplessness

Six’s size relative to the world represents the internalized powerlessness of childhood trauma. Every jump and climb is a struggle against an overwhelming environment designed to crush her.

This physical vulnerability reflects emotional fragility. In trauma, children feel small not because they are literally tiny but because they lack agency. Little Nightmares externalizes this feeling by placing players in spaces built for giants.

Climbing as Assertion of Will

Each climb is symbolic defiance. Scaling furniture, escaping cages, or reaching forbidden spaces represent moments of regained control. The act of climbing transforms fear into motion—turning helplessness into survival.

4. Hunger as the Manifestation of Emotional Need

Throughout the game, Six experiences bouts of hunger that grow increasingly disturbing. At first, she eats bread offered by another child, then raw meat, and later something unspeakable.

This recurring hunger is not just physical—it’s symbolic of emotional starvation. Trauma often leaves victims desperate for affection, validation, or control, and the game portrays this craving through visceral imagery.

From Nourishment to Cannibalism

As the hunger evolves, it loses its innocence. By the end, Six’s need becomes predatory, suggesting that prolonged deprivation can turn victims into aggressors. This mirrors real psychological cycles where those who suffer trauma sometimes replicate harm as a means of coping.

5. The Adults as Monsters of Distorted Care

The adults in Little Nightmares embody twisted archetypes of guardianship. They represent authority figures who should protect but instead manipulate, exploit, or destroy.

The Janitor – The Suffocating Caregiver

The Janitor, with his long arms and bandaged eyes, reflects invasive, blind control. He gropes through the dark, desperate to “catch” Six, symbolizing how abusers impose dominance under the guise of care. His blindness represents emotional ignorance—the failure to truly see a child’s needs.

The Guests – The Indifferent Crowd

The obese guests who feast without restraint symbolize societal apathy. They devour endlessly, caring only for consumption, reflecting the collective indifference to suffering.

6. The Lady and the Mirror of Repression

The Lady, the final antagonist, represents internalized trauma—particularly the oppressive power of self-denial and identity suppression. Her mask conceals emotional wounds, and her control over the Maw reflects how trauma transforms victims into their own jailers.

The Mirror as Symbol of Self-Recognition

When Six confronts the Lady using a mirror, the battle becomes metaphorical: confronting reflection as a way of facing repressed pain. The mirror’s light breaks the illusion of control, showing that fear loses its power when it is recognized rather than hidden.

The Cycle of Power

After defeating the Lady, Six absorbs her power, symbolizing the inheritance of trauma. The cycle continues—those who were once powerless become powerful, but at a cost.

7. The Role of Silence and Sound Design in Fear Expression

Little Nightmares tells its story without dialogue, using sound to articulate what words cannot. Every creak, rumble, and breath is part of a language of anxiety.

Silence as a Tool of Oppression

The absence of speech represents the silence imposed on children in abusive environments. It’s not that they have nothing to say—it’s that no one listens.

The Player’s Listening Role

Players must rely on their ears as much as their eyes. The act of listening itself becomes participation in Six’s hyper-vigilance, mirroring trauma’s sensory overload.

8. Symbolism in Repetition and Dream Logic

The game’s looping, dreamlike structure reflects the cyclical nature of trauma. Every sequence—from chase to fall to hunger—repeats in slightly altered form, emphasizing the inescapability of fear.

Childhood as a Repeating Nightmare

Trauma does not progress linearly; it replays with variations. The game’s design mimics this repetition, creating a sense that escape is temporary and safety illusory.

The Architecture of the Subconscious

The Maw’s impossible geometry—shifting rooms, floating hallways—evokes dream logic. It suggests that the entire journey unfolds within Six’s fractured psyche.

9. Six as the Embodiment of Corrupted Innocence

By the end, Six’s transformation completes the game’s symbolic arc. She begins as a frightened child but ends as something far darker—a survivor shaped by her environment.

Empowerment or Corruption?

Her victory over the Lady is ambiguous. Gaining power through violence mirrors the way trauma rewrites morality. In surviving, Six also inherits the traits of her abusers.

The Consumption of the Guests

As she walks among the guests absorbing their life force, the metaphor becomes complete: trauma consumes and transforms, leaving no one untouched.

10. The Legacy of Fear Beyond the Maw

Little Nightmares ends not with freedom, but with haunting stillness. The cycle of trauma persists, and Six’s new power does not signify peace—it signals continuation.

The game’s closing sequence, where Six ascends into light, feels less like salvation and more like resignation. She has conquered her oppressors, but at the expense of her humanity. This ambiguous resolution forces players to reflect on the deeper question: can innocence truly survive trauma?

The Player as Witness

By guiding Six, players become complicit in her transformation. They participate in the moral erosion that survival demands, which is precisely the point—empathy and discomfort coexist.

Reflection Beyond the Screen

Ultimately, Little Nightmares uses fear not as a tool for thrills, but as an allegory for emotional endurance. It portrays trauma as both a wound and a survival mechanism, where escape is not about leaving the darkness but learning to see within it.

Conclusion

Interpreting the symbolism of fear and childhood trauma in Little Nightmares reveals a narrative of painful evolution. The game’s grotesque imagery and silence form a language of psychological truth, showing how children process horror through distorted perception. Each monster, room, and shadow embodies a different face of fear—neglect, dominance, hunger, repression.

Six’s journey through the Maw is a descent into the human subconscious, where survival demands compromise. What makes Little Nightmares extraordinary is not its terror, but its empathy—it gives voice to the voiceless and shape to invisible pain. Through its surreal lens, it transforms personal suffering into shared understanding, reminding players that even in the smallest figure lies immense emotional weight.